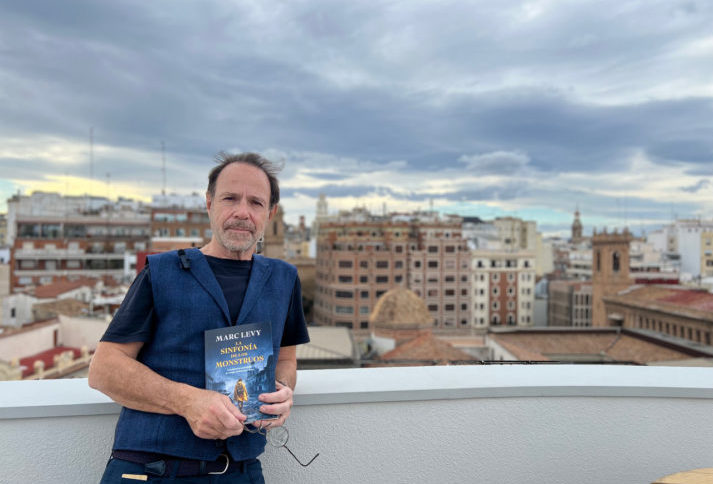

A former company director, Marc Levy published his first novel in 2000, a story that was actually intended for his son. It was his friends who encouraged him to submit it to a publishing house. His first book ‘Et si c’était vrai’ was an instant hit, and Steven Spielberg made it into a film called ‘Just Like Heaven’. Since then, at a steady rate of one book a year, Marc Levy has published 26 novels, all of them topping the bestseller lists in France and abroad. Translated into 50 languages, the world’s most widely read living French author (over 50 million copies sold) was in Barcelona, Valencia and Madrid to present and sign his latest work, ‘La Sinfonía de los Monstruos’ (out in France in November 2023). While the search for identity and love are recurring themes in his novels, this time the writer explores a darker, more political subject, referring to the mass kidnapping of Ukrainian children.

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH MARC LEVY

LAURENCE LEMOINE: It’s a darker, less light-hearted novel, and this time you’ve taken more inspiration from current events, which are rather tragic. Did you deliberately want to change your style?

MARC LEVY: No, because I’ve already changed my style ten times.

I’ve changed worlds, themes and even genres a lot. I’ve written adventure novels, comedies, thrillers, political novels and historical novels.

There’s no premeditation, really. You know, when I start writing, I write about something that’s close to my heart at the time. And it’s often the story that comes to the author rather than the other way round.

The ‘Les Neufs’ trilogy are already very political novels that say a lot about what’s happening in the world today and about political corruption. And in the last volume of the Noa trilogy, I mention the invasion of Ukraine, even though it hasn’t happened yet. It will happen just after the novel is published. And so, when I was made aware through my relations and contacts of the programme of systematic deportation of Ukrainian children by Putin’s Russia, there was almost a kind of urgency to talk about it because I felt it was the subject…

L L: So you also wanted to get involved politically to denounce this reality?

M L: There are many ways of tackling so-called serious subjects. And I’ve always tackled them without taking myself too seriously. In other words, you can approach a serious issue from an angle other than that of seriousness. In fact, that’s often the best way to get readers on board and to draw them into a story. ‘La Symphonie des monstres’ is not a documentary about the abduction of Ukrainian children. It is a tale of adventure and love about a little boy who will do anything to escape, a teenage girl who will do anything to find her little brother and a mother who will do anything to find her two children. But above all, it’s the story of my characters through history.

L L: And we’re dealing with ordinary characters with extraordinary lives or facing extraordinary situations…

M L: Absolutely, yes. That’s exactly it. These are people who are plunged by force of circumstance into an extraordinary situation that is beyond them and who obviously reveal themselves through this in a rather extraordinary way, yes.

L L: There are recurring themes in your work, the search for one’s origins, one’s identity and love too. It’s important and it sells better!

M L: It’s not the search for one’s origins that’s at the heart of my novels, but the question of identity is. I make the distinction because the question of identity is not always to be found in the past. The question of identity is also to be found in the way in which we assume ourselves: assuming who we are, assuming our social background, assuming our sexuality, our tastes, our personality, all this is part of the quest for identity and it is sometimes more nourishing and liberating than knowing that, three generations later, we are descended from such and such a person.

It’s not because love sells better, it’s because without it there’s no point for me. I don’t think there’s a painting, a photo, a dance step, a sculpture, a piece of work done without love that’s not worth sharing. Except for filling in administrative forms, perhaps! So it’s impossible to spend one or two years of your life writing a story without it being imbued with love. In any case, I can’t imagine it any other way. It’s a job that requires a lot of observing, listening and trying to understand.

L L : Writers often have help. They have assistants who research historical facts to put things into context. Does your publishing house provide staff to help you? Or do you use Chat GPT?

M L: No! ChatGPT is really too stupid at the moment! Maybe things will change, but right now ChatGPT is absolutely incapable of finding anything really. There’s one thing you shouldn’t forget about the way ChatGPT works, and that’s that ChatGPT searches for a huge amount of information on the Internet, which is full of errors!

I do my research on my own, and for a very simple reason: 9 times out of 10, you find something you weren’t looking for! So if you outsource the research, you miss out on a lot of details. A novel is usually built on completely unexpected discoveries made during research, which will change the thread of your story, sometimes its course, and even its ending. So, it’s impossible to outsource that. And then there’s one important thing, which is that when you do research to write, a very large part of the research consists of learning.

In other words, I’ll give you a very pragmatic example: you have a character who is a luthier, and you’re going to research the luthier’s trade so that you can talk about it in a credible way. The important thing is not to find the information, but to digest it, learn it and then assimilate it. So if you’re given a book report, you’re going to learn dates that are of little interest to the reader and you’re not going to get into the subject at all either.

And then, very often, research, for example, in relation to professions or skills, is research prior to a meeting with a specialist to whom you ask questions and who shares his time and knowledge. It’s a job that requires a lot of observing, listening and trying to understand too. It’s impossible to outsource. And then, above all, that’s actually part of the pleasure of writing.

L L: And when you’re Marc Levy, are you sometimes afraid of the blank page? Can you be paralysed by the fear of a lack of inspiration?

M L: It depends on what you call the blank page! Lack of inspiration is something else! You have to demystify the blank page: it’s an integral part of every writer’s daily life. There isn’t a writer who sits down at his desk and already knows the 350 pages of his novel. And during the writing phase, you’re constantly faced with the question: What am I going to say now? Where am I going? How do I unravel it? That’s really part of the job.

A lot of people stop at that. In other words, because it’s a job that requires enormous discipline, the slightest blockage is an excuse to stop working. But in reality, it’s not that you’re blocked, it’s that you’re cooking.

And what I’m telling you exists in many professions. For a cook, there are times when you have to wait for the dough to rise and you can’t do anything until it does. It’s the same for a writer. There’s a moment when you stop writing and you feel like you’re stuck and you think. But if you stop working, then, by definition, the story won’t move forward. That means you have to at times like this, you have to accept that you might spend three or four hours staring at your screen or a coconut tree, wondering how your story is going to progress.

It’s different from writer’s block, which is linked to the desire to create and produce. It’s the syndrome of the little death, the end of inspiration. So it’s obviously frightening; like all deaths, it’s frightening.

L L: When you sell over 50 million copies and your name is Marc Levy, and you become rich and famous, can that be dangerous? Do you look after yourself? How do you deal with it?

M L: First of all, there’s no such thing as a famous writer. There’s no such thing. In fact, it’s the ‘sweetest’ type of celebrity because people know your name but not your face. So, there’s no danger of that. There’s never been any hysteria about writers’ personalities. Very few people are interested. But there is still a form of celebrity, of notoriety to be managed. With money on top of that, it can go to your head. Listen, I’ve had no money at all for a very large part of my life and it’s never been a driving force.

I started my life with the Red Cross. What has been the driving force in my life is creation, imagination. I’m an epicurean, and I’m very clear about the extraordinary privilege I have of making a living from my writing. But I’m not attracted by the glitz and glamour of luxury. I could travel 250 kilometres to eat a good meal, but I’m much happier in a small bistro than in a Michelin-starred restaurant.

L L: Have your relations with critics calmed down?

M L: Criticism has changed a lot, generally speaking. At the start of my career, I had some very harsh critics…because they were annoyed by my relationship with success. Today, it’s different but I’ve always cared. Back then, critics liked to present themselves as supposedly ‘very intelligent’ and existed mainly by saying bad things. They liked that a lot. And then the public got tired of it. Today, most critics talk about the books they liked and don’t talk about the books they didn’t like, whereas it used to be the other way round.

L L: The French Institute organised your trip to Barcelona, Valencia and Madrid to present your latest novel and meet students at the French Lycée. How important is this contact with your readers?

M L: Being a writer is very different from being a singer or an actor because you never perform in front of an audience. A singer is on stage and sings in front of an audience. Actors are on stage and perform in front of their audience or the film crew. In my profession, you work alone all year round. You’re always alone in the workplace.

So, book fairs and meetings in bookshops are important events because they’re the only contact you really have with the public. They are the only moments of interaction and exchange, and they’re opportunities to get away from the loneliness of this profession; the hardest and most important thing about writing is knowing how to cope with that loneliness.

L L: A word about your favourite Spanish authors?

M L: Jorge Semprún to start with and Carlos Luis Zafón too, whom I was a passionate reader of and greatly admired. And then, of course, Cervantes.

L L: How well do you know Spain?

M L: Mostly I know Madrid, because I had a very good friend there, so I went there very often; I know a bit about Barcelona, and this is my first time in Valencia. It’s funny, because when you live in New York like I do, it’s very hard to imagine living anywhere else, but I think the only other city I could live in is Madrid. Like in New York, there’s one thing that’s very special, and that’s that there’s a real mix of people, of nationalities, and then there’s a flavour of life and culture in Madrid. I’m very close to Spain, because I have Spanish origins going back some way. But, yes, it would have to be Madrid.

Interview by Laurence Lemoine (French journalist based in Valencia)

(English translation by Will McCarthy)

Article copyright ‘24/7 Valencia’

More information about Laurence Lemoine: https://www.valencia-expat-services.com/?lang=en

French version: https://lecourrier.es/marc-levy-ce-quil-y-a-de-plus-dur-dans-ce-metier-cest-de-pouvoir-supporter-la-solitude/

Photo credits: CKomValencia

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment