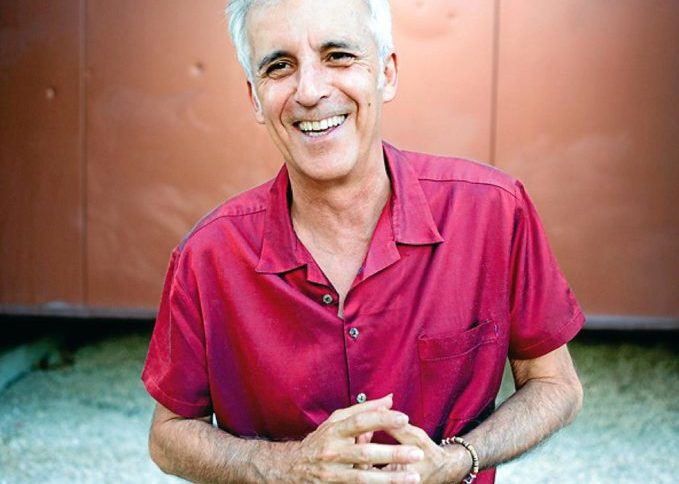

24/7 VALENCIA Can you tell us about your travels around Europe and USA in the late 1960s/early 1970s? Was it an influence on your music?

KIKO VENENO: Yes, I hitchhiked around Europe with a guitar and was busking as a way of making enough bread to survive along the way! This would have been around 1969 onwards, which was an interesting time to be travelling and exploring different cultures outside of Spain. I went to London and Sweden and France too. I was at some hippy music festivals where I saw Joan Baez, Johnny Winter, Mungo Jerry and Pentangle play.

I also went to the U.S.A. and remember spending Christmas in Boston and seeing ‘The Who’ present ‘Quadrophenia.’ Yes, it was loud and Keith Moon was fantastic! In New Orleans, I got to see ‘Dr John (The Night Tripper)’ play a live set during the ‘ Mardi Gras’ Carnival there. I saw the great Bob Dylan playing at a memorable concert in California too. I like that Dylan has kept plenty of mystery regarding his persona over the years, then and now. He does not want to explain the songs, his craft and his art. There is something to be said for that, really. He allows you to make your own interpretations…

You studied philosophy & history at University. All these years later, is there a philosopher that stands out for you?

There are various favourite philosophers. I love Nietzsche for his vitality and humanism and his strong belief in our absolute potential as living beings. He dealt with opposites. So, for example, the person who defines what your liberty is…is actually taking away your freedom! He knew how to make the good out of the bad. Historically, his message has been twisted by some and I’m not interested in those negative interpretations of his work. I look for the positive aspects of his true vision.

In 21st century Spain, there are Spanish comedians like ‘El Gran Wyoming’ and Berto Romero who transmit, in my opinion, a true vision and philosophy of life that is very valid for the difficult times that we live in…

In the world of cinema, I find that the work of film director Icíar Bollaín transmits a vitality and wisdom about life. She combines it with an emotional pull that rings true. It’s not a dispassionate view of life, it’s quite the opposite…it’s intelligent and alive.

I’m still very interested in books about history, including ones that have a different view of the Spanish Inquisition and the conquest of Mexico. I recommend Henry Kamen’s books concerning different aspects of Spanish history and Irish historian Ian Gibson’s books about Spanish culture too.

What was it like being a hippy in Seville in the 1970s?

“Sevilla tiene un color especial” is a well-known song…but it’s a lie. What Seville really has is a sonido especial…a special sound. In those days, there weren’t many hippy characters in Seville but we did make a significant difference to the music scene, I feel. Our tight circle included the iconoclastic band ‘Smash’, which had Manuel Molina as a singer. He was a gypsy guitarist and composer from a family of flamenco musicians and he later formed the legendary Nuevo Flamenco duo ‘Lole y Manuel.’

Can you tell us about working with Raimundo & Rafa Amador of ‘Pata Negra’ fame on your collective debut album ‘Veneno.’ It has a warm feel to it…

Yes, there is a warmth on that album that reflects how open our hearts were on a musical level. We looked out for each other. I was university educated and a middle-class hippy, of sorts, from a respectable part of Seville. The Amadors were gypsies from the poorer and marginalised barrios, on the outskirts of the city. The gypsy’s tesoro (treasure) has always been their music and a natural mastery & feel for rhythm and melody. The Amador brothers were open to me and it was a mutual feeling and that communal vibe is reflected in the music we made in ‘Veneno’. It was a special time. These days, you wouldn’t find gypsies and hippies uniting in Seville with such openness and generosity of spirit.

You also collaborated with the most legendary flamenco singer of all time… ‘Camarón de la Isla’ on his groundbreaking album, ‘La Leyenda del Tiempo.’ How did you find Camarón de La Isla?

Personally, I found Camarón to be a sweet and friendly, rather approachable person…amigable y muy cercana. He was on a mission, which was his singing …that combined so well and powerfully with the music. He had a quiet authority about him and a special aura too. I never ever heard him raise his voice to communicate what was needed. He never needed to shout to make his point. He was an exceptional person. There was magic there, in his art. Camarón de La Isla was a natural. He was a prince and he was a martyr.

Were the 1980s a difficult time for you?

Yes, they were. My music was guitar-based and was not at all fashionable in that period, what with all the synths for electronic music in that era. I remember releasing a maxi-single with tracks combining guitars with techno but it was a difficult time for me.

I had wanted to live as an artist but I was just not making enough to live from music by then. To pay my rent, I ended up working for a ‘Diputación’ as a programmer of cultural events, like theatre shows and arts & crafts fairs and music concerts. I was sent out to pueblos in the back of beyond that I would never had visited otherwise…and that’s saying something, since I thought I already knew Andalusia pretty well by then!

However, what I did learn from that rather austere period (for me) was to have faith in my music and to have a certain discipline with my songwriting and recording too. I bought myself a ‘Tascam’ 4 track recorder and continued to stockpile my compositions for the future. By the 90s, guitar music was back in fashion again (this time for good) and I was then able to release my music more easily.

What are your memories of working with cult music legend Jonathan Richman?

He’s great! ¡Es un crac! We did a show together at ‘The Knitting Factory’ in New York and another one together in Seville, a city he really took to. He sings in Spanish as well! Es un loco! Really, what more can i say about him? He is truly unique!

Can you tell us something about time spent with singer-songwriter Jackson Browne?

He really liked a Spanish version I had done of his famous song ‘Take It Easy’ …I was then invited to play with him in Los Angeles along with David Crosby too, which was a real honour and exciting! Across the Atlantic, Jackson Browne ended up staying with me plus family at a place I have in Cádiz in Spain, for a few memorable days. There were lots of conversations, especially about music…during long and enjoyable dinners with pretty good food too!

What does Lorca mean to you?

The other evening, one of my best friends said to me: “Lorca is not Spain’s finest poet…it is Miguel Hernández .” I had to disagree and have my say:“ Lorca is the greatest Spanish poet.” I would say that Antonio Machado was the wisest poet and Miguel Hernández had the most heart. However, in my opinion, Lorca had the magic and creativity and ability to transmit a poetic vision that is really quite unique. His scope was extraordinary. His fluidity with words was such that some of his best work can be found in the dialogue of his plays for theatre.

Could you tell us how your song ‘Volando Voy’ came about?

It was a song that came about quite casually and in a simple way, it wasn’t an elaborate process at all. Initially, I had the verse:“Enamorao de la vida anque a veces duela.”

One evening, i was at a fiesta with the Amador brothers of ‘Pata Negra’ and i started improvising ‘Volando Voy’ with just two chords on the guitar. It was a canción that nacio encantada…that came about quite naturally and joyfully too. It’s a rumba that is neither flamenca or cubana, it’s kinda somewhere between the two. The roots of rumba are from the Son Cubano. La Rumba Catalana came from that…with musicians like ‘El Pescadilla’ and ‘Peret’ giving the rumba a more Spanish, flamenco feel.

Tell us some more about the song ‘Un Mercedes Blanco’

It’s a Romancero Gitano, which is a typically Spanish form of verses that rhyme in pairs of 2 and 4 and so on. It’s partly a song about the evils of heroin being introduced to the gyspies, living in the marginalised communites of Seville and the South of Spain in the 1980s. Within 5 years of its introduction, many gypsy families were being affected by this awful plague.

What is your view about the use of drugs? You lived through an era of liberty in Spain before the downfall…

Growing up in the hippie era, the drugs of choice were cannabis and LSD. In our own way, we saw taking those drugs as a shared ritual and a way to expand your consciousness. When I saw heroin arriving on the scene, it scared me and I panicked and I kept away from it. I saw heroin as a drug that enslaved people very quickly. It took away their willpower. Heroin is a terrible drug.

Can you take us through the songs of your album, ‘Sombrero Roto’

On this album, I wanted to combine mostly electric sounds with just a little bit of guitar here or there. There’s not actually that many guitars on this album. There is guitarra flamenca, mostly by my guitarist Diego on a few of the tracks, and an electric guitar that I played on a couple of songs too. I basically did the album on my own with my computers, at my home studio, in the Seville area. There’s plenty of keyboards and underlying electronic rhythms on this album, which is not my typical sound at all but it is still me somehow. I grew up fusing Flamenco and Rock sounds. So, I thought I would try something different this time around!

La Higuera is a very sexual song. In Spain, ‘El higo’ is a reference to a woman’s vagina and this song is a homage to women “desde Cadiz a Gerona…y desde Galicia a Formentera.”

Autorretrato talks about all of my defects. When you are open to people about your faults. you are more likely to receive their empathy …as you are showing your more human side, which we all relate to.

Vidas Paralelas is about the impossibility of people really knowing each other, in this Instagram-type world that we live in. Some people are sort of stuck with an over-dependence on social media and being partially blinded by it too. For example, if you read ‘ABC’ newspaper everyday…after a while you end up believing everything they say and no longer think outside the box. If you get the chance to travel, you are more likely to open your eyes to other angles, views and possibilities about life in general.

Chamariz is about a little yellow and green bird known colloquially in Spain as ‘Verdecillo’. It’s a ‘cuplé’ like the songs sung by Conchita Piquer of times gone by. El Chamariz is the sort of bird that you will find resting on telephone lines & television satellite dishes. It sings badly but with a lot of presence. I can relate to that!

Yo Queria Ser Español starts off with a recording of the police trying to break up a demonstration. It’s a reflection of the tensions all over the Spain of today and yesteryear.

Obvio is a simple love song. If you ask me what the secret of success is, regarding being happily married for forty years…when I met Anna there was a rapport and a mutual empathy. There was a sense of wanting to share our lives, as things developed. I always say that love is like a building that you have always to keep working on. Love is strong but it requires work and devotion.

Sombrero Roto is a reference to the ‘Deliquentes’ song I did on the ‘Veneno’ album in 1977…

“Me quiero asegurar / Que mi sombrero está bien roto y así los rayos / Pueden entrar en mi cabeza”

If you always live in your comfort zone, you are not going to learn anything new. Being more open to adventure or a new way of seeing things does have its risks, but you learn more that way and especially from difficult situations. Having cracks…that’s how the light gets in!

Ojalà is inspired Rudyard Kipling’s ‘The Jungle Book.’ I’m imagining the loneliness of Mowgli being in a modern shopping centre instead of enjoying being in nature…

Titiri is like an alegría from Cádiz with an infectious groove. It’s a song to enjoy and dance to.

Miss You is a song mostly sung in English about missing someone and one of the very few I have done in that language. Unlike the other tracks on the album, this song was done live in a studio with a circle of musicians standing around a table with wine. It was done in one take and you can pick up on the party atmosphere too. I was not trying to be profound with this song…it’s more of a case of just having fun with the couplets and sounds of the English words:

“Miss you

I miss the tone of your telephone

Miss the way you fly

Miss you

I miss the sweat and when we met

I miss your smile

Miss you

I miss your skin

Your shiny thing…”

Can you tell us more about your Spanish guitars?

The Spanish guitar has a mature and sweet sound. However, I also enjoy playing steel-string acoustic guitars, especially live, and I have some from ‘Alhambra Guitarras’ in Alcoy that I would recommend. For flamenco guitars, I love playing ‘Guitarras Francisco Barba’ from Seville.

Could you tell us something about your very latest album,’Hambre’?

When I started composing for ‘Sombrero Roto’ I ended up with twenty-two songs. I chose the ten that were most ready, but the others kept going round and round in my head and I felt that they were growing and maturing, getting somewhere. Songs need time to develop. When they were finally ready, I mixed them with new songs, like ‘Hambre’, ‘Días raros’ and ‘Madera’, and even with earlier songs, like ‘La felicidad’, which comes from a long time ago. For me this new album has been like a challenge, to actually enter the sacred terrain of flamenco, its majesty, singing flamenco melodies… that is a ritual of sorts. Entering this world has been incredible, it has been very difficult for me to get inside the music and truly express myself in this way and I am very happy with the results. Because this time around it’s not the simplicity of the compositions that I want to display, I want to show that I can sing in harmony with the “voz” of flamenco music, with its feeling and its emotions.

How did it feel to be awarded prestigious titles & awards like ‘Medalla de Oro al Mérito en las Bellas Artes’ and ‘Premio Nacional de Músicas Actuales’?

My mother always loved music and was always singing at home. In contrast, my father was a military man who had been based in North Africa when Franco did his ‘Golpe de Estado’ in the 1930s. My father never felt that I should be trying to be a musician, especially as a way of making a living. He thought that I was distracting myself and that I should train to be a doctor or lawyer or something respectable like that. However, when I started being awarded those titles, his attitude changed. With hindsight, he had the grace to say that I had been right all along in dedicating myself to music!

Interview by Will McCarthy

Article copyright 24/7 Valencia

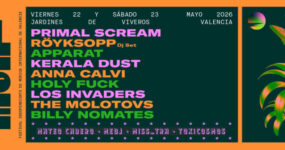

KIKO VENENO PLAYS PLAZA AYUNTAMIENTO WITH ARIEL ROT ON SEPTEMBER 23rd AT 22h.

More info: https://247valencia.com/festival-diario-es-from-september-22nd-to-24th-valencia/

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment