Amidst the office blocks, stadiums and beach bars of Valencia, the legacy of Al-Andalus lives on. Valencia, one of Spain’s oldest cities, has been washed over by the tides of history, and each successive wave of empires and religions have all left their mark in its walls. The city surrendered to the Berber and Arab forces in 714, led by the great General Tariq-ibn-Ziyad, after whom the rock of Gibraltar was named, where Tariq’s forces first landed from North Africa. Jabal al-Tariq meaning the Mountain of Tariq, has become hispanised to Gibraltar over the centuries.

However the walls that have seen the rise and fall of empires, caliphates and kingdoms almost came crashing down, never to endure to this modern age. The first emir of Cordoba, Abd al-Rahman I, ordered the city destroyed in 755. Luckily for all of us in love with Valencia’s vibrant energy and culture, these orders were never carried out and several years later his son, Abd Allah, had a form of autonomous rule over the province of Valencia. He established a palace on the outskirts of the old city named Russafa, giving the name to the neighbourhood Ruzafa, the site of many modern watering holes where one can obtain the notorious cocktail Agua de Valencia.

When the Muslims arrived in Valencia they found a city of decadence and with a vast gulf between rich and poor, a weakening population and a city that was collapsing in on itself, rather than expanding. There are very few examples of written or archaeological accounts of Valencia from this period, highlighting its limited importance. Under Muslim rule the city flourished, with a roaring trade in paper, silk, leather, ceramics, glass and silver-work.

Valencia has had many names over the years. Founded as Valentia Edetanorum “the city for the valiant” by Consul Junius Callaicus for his loyal soldiers, this name was continued by the Visigoths. However with the arrival of the Islamic Caliphates it was named Medina al-Turab (City of Sand). However in the 10th century, the city received the name Balansiyya, adapted from the original Latin name, the hispanised version of which we now know the city by today.

In the 11th century Balansiyya was reborn with the creation of the Taifa of Valencia kingdom following the death of al-Manṣūr (Almanzor), the chancellor of the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba and de facto ruler of Islamic Iberia. Despite the chaos that followed the chancellor’s death and the disintegration of the caliphate into taifas (independent Muslim kindoms and principalities), the town grew, and during the reign of Abd al-Aziz al-Mansūr a new city wall was built, remains of which can be seen today throughout the Old Town (Ciutat Vella).

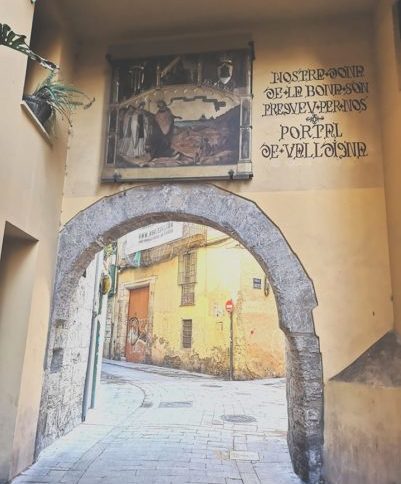

The star-shaped layout of Ciutat Vella also bears the mark of Muslim influence, as the star is often used as a symbol for Islam in conjunction with the crescent moon. Its streets are built on top of many of the original streets laid down by the Moorish architects, with narrow streets and high roofs to provide maximum protection from Valencia’s blazing summer sun. A key example of this is Portal de Valldigna street. Further instances of Islamic architectural legacy are abundant in Valencia such as the intricately carved entrance to the Baños del Almirante bath house and even the Cathedral and the tower, El Micalet (El Miguelete), originally constructed as the minaret of the old mosque, which stands sentinel over the Plaça de la Reina.

In 1011 Mubarak and Muzaffar took possession of the city. By increasing taxes they made some reforms and urban improvements, but were ousted in 1021 by a popular revolt that placed the grandson of Almanzor, Abd al-Aziz ibn Abi Amir, upon the throne. With him the city enjoyed a period of splendour. The Roman geographical expansion was replaced by demographic development and new walls were constructed, turning the city into one of Al-Andalus’ strongest fortress cities. It was also a melting pot of all a multitude of cultures and ethnicities, with groups arriving, living and working in Spain and Valencia from all over the Islamic empire; Jews, Turks, Sub-saharan Africans, Slavs and more. Unlike its Christian neighbours, Al-Andalus (to call it by its islamic name) was much more tolerant of diversity.

In 2019, work on a social housing project in the El Carmen neighbourhood of the Ciutat Vella uncovered the remains of an Islamic necropolis, with the remains of 13 islamic burials excavated from within its walls. Archeologist Aquilino Gallego identifies this discovery as part of the Bab al-Hanax cemetery which dates back to the 11th-13th century. A €35,000 excavation project was undertaken to extricate the remains of both the necropolis and the deceased so that the housing project could go ahead. Luckily for the residents of Plaçe de L’Arbre, in Islam the souls of the dead do not return to the land of the living until the Day of Resurrection, so they can sleep soundly in their beds without the fear of hauntings. In 2010 a hotel developer, Luis Bellvís, also discovered the foundations of the old Muslim fortifications when breaking ground on a new building project, the Hotel Palacio Marqués de Caro. Part of the old wall still stands in its original spot inside the hotel

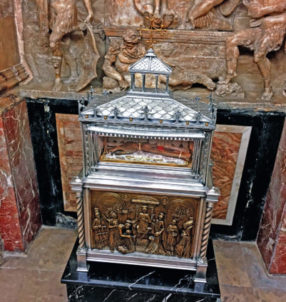

Following this trend of the new being built over the remnants of the old, Valencia Cathedral is built on the site of what was once a Roman temple to the Goddess Diana, which became a Visigothic Cathedral then a Mosque before being once more dedicated to Christianity. It is recorded that the mosque/cathedral remained standing for 30 years after the conquest of the city by the Christians in 1238 and with Quranic inscriptions still engraved into its walls. In 1262, the then bishop Andreu d’Albalat began its destruction and the creation of a new cathedral in its place. Valencia’s Cathedral is notably more sobre and less grand than many of its brethren, a fact which has been attributed to the need to erect it quickly to mark the Christian victory over the Muslims, and that it was built on the budget of the local bourgeoisie, without access to a King’s treasury. Jewish glass craftsmen secretly incorporated a Star of David into one of the stained glass windows, which avoided the eyes of watchful Christians for centuries.

No, I’m not going to put a picture of it here. Yes, you will have to go find it for yourself.

The end of the 11th century and the better part of the 12th century would see Valencia pass back and forth between Christian and Muslim hands. The Castilian nobleman Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid (an Arab title- al-sīd, meaning The Lord) entered the province of Valencia at the head of an army composed of both Christian and Moorish soldiers and laid siege to the city in 1092. After two years of siege El Cid had carved out his own principality with his conquest of Valencia, which he ruled over until 1099.

The city remained under Christian control until 1102, when the Almoravids retook the city and restored the Muslim religion. Although Alfonso VI the self and prematurely styled ‘Emperor of All Spain’, drove the Muslim forces out of the city, he was unable to hold it. The Almoravid Mazdali retook Valencia in 1109. The declining power of the Almoravids in the middle of the century coincided with the rise of a new North African dynasty, the Almohads, who took control of Al-Andalus from the year 1145. The Almohads would not gain entry into Valencia however until 1171 as they were fiercely resisted by Ibn Mardanis, King of Murcia and Valencia. The two consecutive Muslim dynasties ruled Valencia for over a century.

The Spanish language is sewn through with additional descendants of the Arabic language. For example, the phrase Ojalá (Hopefully) comes from the Arabic insha’allah (God willing). In actuality, if you ask someone to do something for you or to meet them at a later date, and they respond with insha’allah, don’t hold your breath. These days it’s just a polite code word for no. Alfombra, Almohada, Albondigas (carpet, pillow, meatballs): these are all words that have their origin in Arabic, as does any Spanish word that starts with the prefix Al-, meaning ‘the’ in Arabic.

The successive Arab, Berber and North African dynasties brought complex irrigation systems to the Iberian peninsula, stemming from practices in the North African desert. By rechanneling the Turia and Xúcar rivers, the Moors kickstarted Valencia’s agricultural development, making its terrain extremely fertile for growing sugar cane, almonds and even rice. This would be the foundation for cuisine that would become an integral part of the Spanish, and in particular the Valencian, gastronomy. The Spanish word for rice, arroz, comes from the Arabic rūz (رز). Without the transportation and planting of rice by the occupying forces, Valencia’s signature dish paella, might never have existed. What a tragedy that would be for our collective taste buds.

Furthermore aceitunas (olives) comes from the Arabic zeitūn (زيتون), the word and the tasty fruit brought to Spain first by the Romans and then diversified by the Arabs. In addition, the word for oil aceite comes from the Arabic zayt (زيت), and as my Madrileñan Grandma always says, “a meal not cooked in olive oil is a meal not worth having.” If not for the arrival of the Islamic Caliphates and all they brought with them in the form of architectural styles, cuisine and language, Valencia’s sights, sounds and tastes would be a far cry from what they are today.

Report by Danny Weller

Article copyright 24/7 Valencia

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment