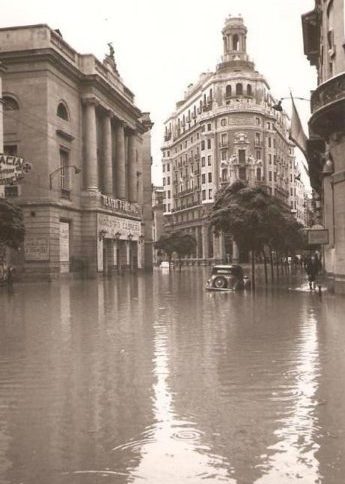

This 14th of October marks the 66th anniversary of “La Riada de Valencia”, the flooding of the River Turia in 1957, which left 81 people dead and three-quarters of the city’s streets underwater.

Just like all cities built on the banks of rivers, Valencia suffered an eternal paradox: a river is a source of life and economic prosperity, but also the source of serious damage from sporadic flooding. In the autumn of 1957, what had once been a trickling brook winding through mudflats, broke its banks after a weekend of torrential rain, sweeping through Valencia’s streets, leaving devastation in its wake. Residents were forced to climb up buildings, lampposts and statues to escape the clutching waters. That autumn, the meteorological phenomenon “the cold front”, which was becoming common in Western Europe at that time of year, generated a series of long lasting and intense precipitations, torrential rains or even hail storms. This led to the swelling of rivers and the flooding of the land surrounding them.

Over two thousand years ago in the year 138 B.C, Valencia was founded by Roman Consul Junius Callaicus on a small river island, five kilometres from the shores of the Mediterranean. According to the journalist Vicente Aupí, Valencia had suffered 75 instances of flooding in the last seven centuries even as close to “La Riada,” as 1949. However not once did the waters reach the interior of the city, until the flood of ‘57 which changed the face of Valencia as we know it today.

The rains began on Saturday the 12th October, the National day of Spain, and were especially strong in the interior, around Llíria, where they were receiving around 215 litres of rainfall per metre squared per hour. However in Valencia they were only receiving three litres per m2 per hour, so no-one was ringing the alarm bells just yet. Meanwhile, for thirty hours straight, areas such as Requena, Buñol and Chelva received almost 500 litres/m2 per hour. This vast quantity of water charged down towards the sea, taking with it the water from its tributaries, flooding roads and bridges and blocking off channels meant to aid with drainage.

On Sunday the 13th, those alarm bells began to sound, and the Mayor of Valencia, Tomás Trénor Azcárraga, in communication with the Civil Governor, Jesús Posada Cacho, put the State’s security and emergency services into a state of high alert. Ironically, it had just stopped raining over the City of Valencia: the calm before the storm.

In the early hours of Monday morning, the waters of the Turia began to rise. At 3am the first wave struck, causing the initial flooding, with the river clocking speeds of 2700 m3 per second. This first wave only affected those residents who lived along the banks of the river and the areas near the sea in Malvarosa and Nazaret. In deathly silence, the already swollen river spread across the river bed sliding its way up the containment walls, up the balustrades of beautiful stone bridges like the Puente de Trinidad, while it had already washed away wooden bridges like the aptly named Pont de Fusta. Soon it would appear as yet another occupant of Valencia’s streets.

Then the rains returned with torrential force, causing the river to swell until around midday, when the second wave struck, even more powerful than the first. The Turia was flowing at 3,700 m3 per second. Not even the Nile flows that fast. With this surge of water the river returned to its natural course, right through the city centre, which due to the city’s expansion and the use of the Turia for agricultural irrigation, had run dry since the 11th century.

Yet now the river returned home with a vengeance. The city’s sewers, which for years had emptied sewage onto the river bed, raising it higher, pumped fouled river water straight back into Valencia’s streets. Some reports indicate that manhole covers shot into the air followed by a violent explosion of muddy water as the water returned to the city one street at a time. In some areas like the Calle de Doctor Oloriz, the water level reached up to five metres, forcing residents to desperately scramble for higher ground. Residents who, despite the abundance of water flowing around them, mocking them, had no access to drinking water or electricity, and were completely cut off from the rest of Spain, and the rest of Valencia. The waters of the Turia officially claimed the lives of 81 Valencians, (the true number is thought to be closer to 400), left an uncountable number injured, and caused economic losses of thousands of millions of pesetas in homes and livelihoods.

Curiously the flood waters left the old Roman part of the city completely untouched. The Plaza de la Reina, the Plaza de la Virgen and the Carrer del Micalet for example were exempt from the Turia’s clutches, and Callaicus’s island fortress city of “Valentia Edetanorum” seemed to re-emerge from the depths of history.

In the following days, the army was brought in to help deal with the disaster, with citizens being airlifted to safety from the top of buildings and patches of dry land by helicopter. Much of the city, beach and port were covered in a thick layer of mud which took the army and the citizens of Valencia until the end of November to remove. Spain’s fascist dictator Francisco Franco arrived in Valencia on the 24th of October, when much had already been cleaned to survey the situation and gain some political points by showing his face in a disaster zone.

This “cold front” in ‘57 would be the last straw, as it provoked the creation of a project to protect the city from future flooding, namely “The South Plan”, a preventative measure which diverted the course of the river around the south of the city, leaving the section of the river running through the city centre to run dry. This gave the opportunity for Valencia’s development. Initially, in an effort to alleviate traffic in the city, the local government put forward plans for a highway system in the heart of the City. However this met fierce resistance from Valencia’s citizens who protested the highway proposal with the cry, “The bed of Turia is ours and we want green!”

By 1980, the City approved legislation to turn the riverbed into a park and commissioned Ricard Bofill to design it in 1982. The plan created a framework for the riverbed and divided it into 18 zones, each with its own architectural style. El Jardín de Turia is five miles long and is the longest park in Europe, and has transformed the face of Valencia, boasting bike paths, event spaces, playing fields, fountains, lakes and impressive structures such as Santiago Calatrava’s biomorphic City of Arts and Sciences. Thus out of tragedy came a new artery in the lifeblood of Valencia.

Report by Danny Weller

Article copyright 24/7 Valencia

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment