##Youth culture and Rock ‘n’ Roll are not concepts we easily associate with post-war Franco’s Spain. It’s hard to see where they would fit in amongst the grey public works, the development plans and the authoritarian grip of the regime. In the late fifties, at the end of the grim period of total isolation and with the “economic miracle” about to happen, football, toros and cinema were tolerated and even encouraged by the regime. However, swinging your hips to the rhythmic racket of a bunch of rowdy adolescents was definitely not in the script. Yet despite the best efforts of the Caudillo’s censors and the tight rein the Catholic Church held on the nation’s morality, Spain was not completely bereft of bequiffed teenage rockers on the make and one of the most celebrated was a young Valencian who went by the name of Bruno Lomas.

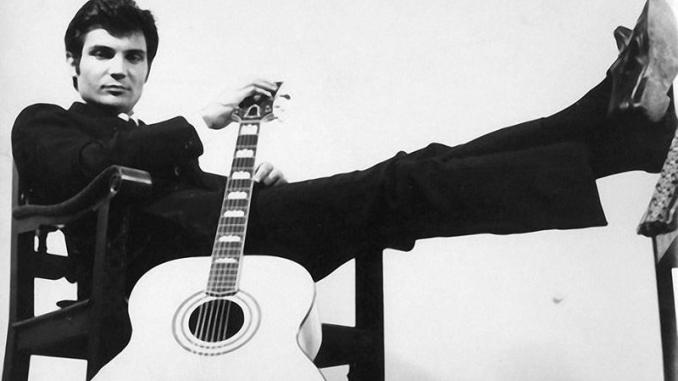

He was born Emilio Baldovi Menendez in Xativa on the 14th July 1940, just a year after the end of the Civil war. His father was a military doctor and he was educated by Dominican monks in Valencia and all was set up for him to study law; a perfect son of the new Spain. Then, at the age of seventeen, he discovered Gene Vincent. Like many of his generation, films and music from outside of Spain and interaction with the first tourists to arrive to the then unspoilt Spanish coast had shown him that there was something else to aspire to. Hollywood and Rock ‘n’ Roll offered tempting pleasures, which were not entirely in tune with the dictatorship’s way of seeing things.

By the time Bruno Lomas had formed his first band with some of his schoolmates in 1958, Spanish audiences had already been exposed to foreign pop music in the guise of crooning Cuban exile Antonio Machin and vocal bands like the Cinco Latinos. However, it’s hard to imagine that Lomas and his friends thrashing out “Be-Bop-A-Lula” at his first gigs in Valencia would have been anything less than a shock to the system for the Valencian audience, most of whom had never experienced Rock ‘n’ Roll before.

He went down a storm and in 1960 he formed a new band “ Los Milos” who made their first recordings that same year and quickly became the biggest act in Valencia, playing and recording Spanish versions of American and Italian hits. It wasn’t long before he was noticed by French promoter Johnny Stark who persuaded Lomas to tour in France. The rest of the band couldn’t envisage a career in music and didn’t want to move away from Valencia so Lomas was set up with a new band calling themselves Los Diávolos, who toured France with great success in the summer of 1962. He came back to find that Los Milos had released one of his old recordings, the gloriously Valencian sounding “Twist a Maria Amparo”, behind his back and even used his picture on the cover. Lomas was furious but it became his first number one.

The Diávolos changed their name to Bruno Lomas y Los Rockeros. They went back to France in 1963, playing more than 100 concerts in 11 months (including two gigs at the Paris Olympia) and releasing two singles. By the time they returned triumphantly to Valencia at the end of that year they were earning 80,000 pesetas a month when the average wage in Spain was just over 5,000. They had honed their craft and had a sound system no-one in Valencia could match and in 1964 they blew all local bands out of the water.

Changes in Spain were in full swing. The regime was keen to show the world a new image. Franco increasingly left his military uniform at home and changed his Falangist entourage for a group of technocrats and economists. He developed a new persona and created the fiction of a sort of father of the nation. Spain had joined the UN and the World Bank and cemented ties with the US Foreign investment and aid poured in. All of this, coupled with the technocrats’ succession of development plans and the fact that five million Spaniards were living and working abroad, meant that Spain could claim to have a state of full employment. The arrival of richer European tourists and the experience of the Spaniards working abroad brought foreign currency into the country and, equally importantly, started to change people’s attitudes.

Bruno Lomas’s generation had work and a small amount of disposable income and wanted to have some fun. The fashion of the day was the Guateque or house party where on Saturdays and Sunday afternoons middle-class kids would take advantage of their parents going away to the country to invite friends round to listen to records and drink Licor 43 or new imported soft drinks like Coca-Cola or Pepsi. These were the people buying Bruno Lomas records and in the mid-sixties they bought barrowloads of them.

The band went for the rock star lifestyle, buying expensive sports cars resulting in run-ins with the authorities over speeding and living it up too much but they never made any political stance against the regime. They were not alone amongst many young rebels in Spain at the time in that their motivation was more hedonistic than ideological. In 1965, the band signed to EMI’s Spanish label Regal and had 7 successive hit singles… some written by Lomas & some versions of American and British hits.

In 1966, Lomas decided to change tack. He wanted to widen his appeal and go for the pin-up market with schmaltzy orchestral ballads. This went down like a lead balloon with the rest of the band who wanted to stick to their Rock’n’Roll roots and they went their separate ways in June of that year. Lomas went mainstream and initially had huge success, recording some of his biggest hits and even making a few films. He was also the first Spanish rock star to release a live album. By 1968, however, he was no longer the flavour of the month and, having turned his back on his original audience, his career started to slump. He had a few throwaway summer hits in the early Seventies but this was the start of a slow and painful decline. Spanish youth had moved on and he was looking distinctly old hat when compared to the popular politically-motivated cantautores (singer-songwriters), whose songs pushed for liberty and democracy.

The former enfant terrible rebel rocker was part of the regime and the regime was about to come to an end. He was out of date and out of step. This was only exasperated by his defence of Franco at his concerts and, later, in the first years of democracy by his flirtation with right-wing politics and Fuerza Nueva. But there was still yet to be one final triumph, his very own “68 Comeback Special”. It took the form of a concert in the Sala Jacara in Madrid where he performed in front of the great and the good of the Spanish music industry and the young scenesters from ‘La Movida Madrileña’. He went back to his Rock’n’Roll roots and brought the house down. Despite the success of the concert, there was to be no revival and he spent the last years of his career touring the “Bruno Lomas Show” through smaller and smaller venues until, in August 1990, he was killed when he crashed his sports car in the Valencian seaside town of Puebla de Farnals on his way to play a concert in Lliria.

Many believe the seeds of Spain’s transition to democracy were sowed in the social changes that took place at the beginning of the sixties but, by the time the transition arrived, the man who was a living symbol of these changes was washed up and left behind.

David Rhead and José Marin