Valencia Renaissance Woman

Isabel de Villena was born in 1430 in Valencia, the illegitimate daughter of an alchemist wizard. She was an author, nun, ambassador, and a leading and inspirational figure in Valencia cultural life, and Isabella la Católica’s auntie to boot. A renaissance woman in every sense.

Isabel was just four years old when her father Enrique de Villena (a kind of cross between a real life Dumbledore and a primitive mad scientist) died. Enrique was an astrologer and self-proclaimed alchemist wizard who had escaped religious persecution due to his royal connections (he was the grandson of Henry II of Castile) and was protected by both the Aragon and Castilian courts.

This left him relatively free to get up to all kinds of mischief. Numerous ‘scientific’ experiments he carried out are documented, mostly related to medicine, the supernatural and the existence of spirits. Legend has it that his last great experiment was an attempt to cheat death itself.

After he passed away in 1434, he left instructions for his servants to keep his death a secret and chop his body into strips. These strips were to be kept for nine months in the cellar of his house conserved in pots stuffed with aromatic herbs after which, (Shazaam!) he would miraculously come back to life. We’ll never know if old Enrique had actually discovered the secret of eternal life as this was just one jape too many for the influential hierarchy of the church. As soon as they found out about his little experiment they had his remains, books and doting servants all thrown on to a bonfire. Only a few of his books on alchemy, medicine and medieval magic were saved for posterity by his friend Lope de Barrientos, the bishop of Segovia. They are kept in the national library.

Little Isabel, whose mother had died in childbirth, was now an orphan and was taken in by her cousin Queen María of Castile, the wife of the Aragon king Alfonso V ‘the Magnanimous’. She was educated at the royal palace in Valencia (on the site of what are now the Viveros Gardens). The Valencia royal court was powerful and cultured and largely run by women. While the king and his knights were away fighting numerous wars up and down the Mediterranean, it was the half-English Queen María and her friends who ruled the roost.

This was the perfect atmosphere for a strong, independent-minded girl like Isabel to grow up in and she developed a character far from the acquiescent wallflower damsels in distress of the time. Daughters of the nobility of this period were often merely the currency of court intrigue, married off to whoever suited the political ambitions of the moment as their parents jockeyed for position, passing from obedience to their husband. The acutely intelligent Isabel, who saw most of the men in court as complete buffoons, was never going to settle for such a life, and luckily for she had powerful friends and no scheming parents to answer to.

Isabel’s preferred option of remaining single and presiding over her own life was unthinkable at the time, so she chose the next best thing – she joined a convent. This would allow her to keep her independence and, of course, Isabel was never going to be just a conventional nun. In 1463, Cardial Rodrigo de Borja (later to become the Borgia pope Alexander VI) named her Abbess of the most important convent in the city of Valencia, the Real Monasterio de la Santísima Trinidad located next to the royal palace. ‘La Trinidad’ still stands at the beginning of C/Alboraya opposite the Torres de Serrano between the Estación de Madera and the San Pio V Fine Arts museum.

At the young age of 33 she had become (after the queen) the second most important woman in the city and perhaps the whole Aragon Empire as this was Valencia’s golden age. The city had become the centre of commerce for the ever-expanding Aragon crown and was a magnet for the nobility, artists, writers and merchants. Isabel became a central figure of this renaissance Valencia. In her position as abbess, she became a great patron of the arts and a ambassador for Valencia commerce. Leading merchants and nobles from across the Mediterranean would pay her regular visits. Frequent debates on philosophy and literature and numerous other cultural events were held at the convent and the cloisters of La Trinidad became known as the second court of Valencia. The cultural icons of the time such as Jaume Roig, Joan Roís de Corella, Ausiàs March and Joanot Martorell all attended and were all close friends of ‘‘Sister’’ Isabel.

Not content merely to sit back and listen to the intellectuals, she took an active part in the debates and she herself wrote, amongst many sermons and interpretations of the scriptures, one of the most groundbreaking works of the Valencia Renaissance. Being an abbess it had to be something related to Christianity, but being Isabel de Villena it had to be something a little different.

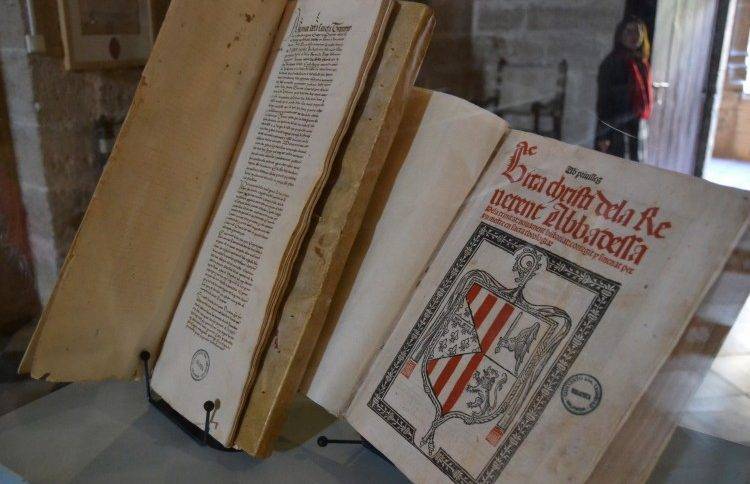

Isabel produced a feminist version of the life of Christ. Often referring to little-used Greek and Roman sources and apocryphal texts, she wrote her take on Christ’s life entirely from the point of view of the women involved in the story. The Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene and other female characters account for 85% of the text. ‘‘La Vita Christi’’ was published in 1495, five years after Isabel de Villena’s death. It was the source of much controversy at a time when the outlook of the Christian establishment was almost wholly misogynistic. It managed to get past the Inquisition, however, due to strong support from the author’s niece, Queen Isabella I la Católica. The book is often acclaimed as the fırst-ever example of feminist literature.

Isabel de Villena died on 2 July 1490 and is buried in the Trinidad Convent crypt. She stands out as one of the few celebrated women of the period and her book survives as an almost unique example of Renaissance literature to be written by a woman. La Trinidad is still a functioning convent and is not open to the public. However, if you are strolling that way down to the Viveros or the other way up to catch a tram, it’s worth taking a look at its 15th century Gothic façade and the beautiful Renaissance decoration around the entrance to the chapel.

David Rhead and José Marin

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment