Recent work on the Metro and the gardens in Gran Vía Germanías and Gran Vía Marqués del Turia have unearthed two almost forgotten 1930s air raid shelters or ‘Refugios’. Completely intact and left nearly exactly as they were at the time of the horrific bombing raids Valencia endured during the Spanish Civil War, their rediscovery is a chilling reminder of one of the darkest and most painful periods in the city’s history.

During the whole tragic conflict (July 1936 – April 1939) only Barcelona and Madrid suffered more bombing raids than the city of Valencia. Between the first aerial attack on 13 January 1937 and the last on 18 February 1939, there were 442 raids on the city and its port. The first victims were 65-year-old Carmen Tatay and her son José who were killed while walking outside their home in Carrera del Río near the port. In total, 847 people lost their lives in raids on the city, 2,800 were injured and 931 buildings were destroyed.

At the beginning of the war, Valencians felt far away and relatively distanced form the conflict to the extent that it was deemed necessary for huge signs to be erected in the Plaza del Ayuntamiento (then Plaza Emilio Castelar) reminding people that the front was “only 150 kilometres away”. People went about their business in a kind of semi-phony war atmosphere. All this changed quickly and dramatically. The French border had been closed and by 1937 the Republic was loosing control of the northern coastal ports. When Gijón fell to the Nationalists in October of that year, the Mediterranean coast became the Republic’s only means of trading with the outside world.

While Valencian ports had always been a target for the Nationalists (Alicante and Valencia were bombarded from the sea as early as November 1936), from 1937 onwards they became a focal point of the war. The Mediterranean coast was essential to the Republic both for the import of arms and supplies and the export of goods to keep the war economy afloat. The lucrative export of Valencian oranges alone brought 31.7 million dollars into the Republic between 1936 and 1937. Hundreds of Thousands of tonnes of military equipment arrived from Russia and equally large quantities of coal and other supplies came in through Valencian ports. It didn’t take long for Franco and his allies in the German and Italian air forces to focus their attention on the blockade and destruction of this vital lifeline. In order to do this, the Jefatura de Tierra, Mar y Aire de Bloques (mainly an airbase for Italian and German planes) was set up in Palma de Mallorca. Franco put his own brother Ramón in charge, who was later killed when his plane crashed while on a bombing raid on Valencia.

Throughout 1937 the port of Valencia came under heavy bombardment and the Poblados Marítimos around the port experienced the gruesome effects of ‘collateral damage’. The bulk (more than 70 per cent) of the Republic’s trade was with British registered ships, as 1,033 British ships loaded and unloaded in the port of Valencia during the conflict and 35 British registered ships were sunk while docked in Valencia harbour between 1937 and 1938. The port of Gandia (owned by the British Alcoy and Gandia Railway and Harbour Company) was constantly bombed in this period and almost completely destroyed. Despite the threat to British interests neither the British government, sticking to the dual doctrines of appeasement and non-intervention, nor the four Royal Navy destroyers stationed along the coast made much of an effort to stop the carnage.

The focus then turned to a new weapon of war – the indiscriminate bombing of civilians in order to spread panic and terror, a strategy that was to become all too common during the Second World War. Valencia was one of the first cities in the world to experience it. On 15 March 1937 at 8.00 p.m., calculated as a time when the maximum number of people would be out on the street coming home from work or going off to one of Valencia’s 27 cinemas or seven theatres (all fully functioning until well into 1939), six Italian planes appeared from behind the cloud cover out at sea and dropped around 20 incendiary bombs on the city centre, killing 33 people and injuring hundreds more. The newspapers of the time described the terror, the chaos, the roar of the sirens, the screech of the falling bombs and the screams of the injured, the explosions and the crack of anti-aircraft fire, blood and horror unimaginable in the Valencia we live in today. The same strategy was used just a month later at Guernica and repeated in Barcelona, Alicante and Valencia again. Historian José María Prats claims that Hitler, in a fit of rage over the Republican attack on the German warship ‘Deutchsland’, planned to completely flatten Valencia in May 1937 but was talked out of it.

The most intense bombing came in 1938. On 26 January, 125 people were killed when bombs were dropped north-to-south across Valencia city centre. Just a week previously, 170 had been slaughtered in Barcelona under similar circumstances. In May of the same year, 250 were killed when a market was bombed at 7.00 p.m. in Alicante. The world press expressed their indignation, the U.S. Secretary of State sent a letter of protest to the Nationalist government in Burgos and British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden resigned in protest of his Government’s inaction. Even the Vatican criticised the attack but the bombings continued.

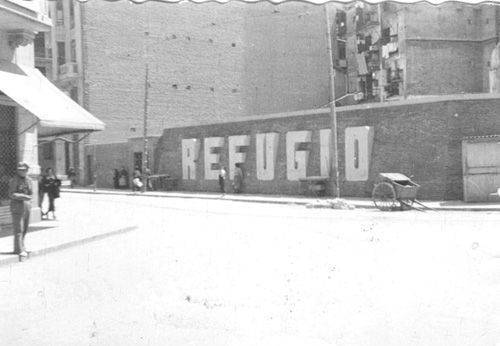

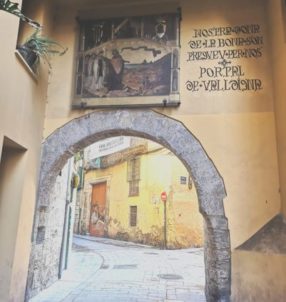

Valencians set about defending themselves. Pamphlets were printed with guidelines informing people where to take shelter during an air raid and which type of buildings was more vulnerable. In July 1937, the civil defence groups ‘Juntas de Defensa Pasiva’ (JDP) were formed in Valencia, Barcelona and Alicante. Their main job was to organise rescue teams, fire brigades and first aid posts, but they were also responsible for the installation of sirens and the building of shelters. The first shelters were built at the beginning of the war in 1936. By 1939, there were 43 specially built shelters in Valencia and another 115 cellars and basements were designated as civil protection areas. The location of each shelter was indicated by a large sign with the word ‘Refugio’ in big, bold 1930s-stye lettering, easily recognisable even to those who couldn’t read. The biggest were in C/ Colon and the port neighbourhood of Nazaret and many of them still survive (the most visible are in C/ Alta, C/ Serranos and Plaza Teutan).

When enemy planes were sighted, often from the observation post at the top of the Miguelete, the sirens would sound for three minutes and at the end of the raid there was a two-minute all-clear siren. Most of the sirens were sold for scrap after the war but one still remains on the roof of a building in C/ Martinez Aloy opposite the Finca Roja.

There were many false alarms, which gave the impression that there were far more bombings than actually happened. False alarm or not, the devastating effect on morale was the same, the terrible panic of the rush to cram into the shelter which people losing their shoes and screaming children who had lost sight of their mothers.

The shelters were mostly built by volunteers and veterans. Towards the end of the war they had to resort to forced labour by prisoners in some cases. Local people were expected to contribute both physically and financially. The walls of each shelter were built with reinforced concrete, bolstered with sand, and ears of corn to further absorb any impact. Inside the shelters there were ventilation ducts and long stone benches. The shelters were often overcrowded. Officially there would be one person per square metre but usually there were four times that many. Smoking, eating and even too much talking (because of problems with lack of oxygen) was prohibited by the JDP. Until the all-clear sounded the tension and the growing stench could be unbearable, but the ‘Refugios’ saved lives and in such traumatic times the mere idea of a safe haven was a comfort to many.

The raids on Valencia, Barcelona and Alicante were forerunners for Coventry, then Dresden and Nagasaki, and later Mostar and Baghdad. In turn, the processes followed and the lessons learnt by the Republic’s JDP became the blueprint for civil defence in London, Liverpool and Berlin. There is no museum in Valencia dedicated to this period of Valencian history. Some prefer not to dig up the past, others don’t want to see it used for political ends. But this is part of what the city and this country is and perhaps the bit of history unearthed on the Gran Via would be a perfect place to remember that.

David Rhead and José Marín

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment