Valencia’s Poblados Marítimos have been through a lot. Over the years they have been destroyed by fire, suffered the worst of the city’s floods, and been flattened by bombs. Not so long ago, the area’s residents had the America’s Cup crowd strolling about and Formula One cars careering around their once peaceful streets and crumbling houses…

The Poblados Marítimos are made up of three of Valencia’s most traditional and most neglected neighbourhoods; El Grao near the port and along the seafront to the North, El Cabanyal and El Canyamelar. El Grao was founded by Jaume I in 1238, on the site of what is thought to be the old Roman port.

Its residents gradually spread out to what was then called the ‘‘barrio de pescadores’’ or fisherman’s district later to be known as the Cabanyal and the Canyamelar. They were painted by Flemish Artist Wijngaerde in 1563 as a small group of ‘‘Barracas’’ (traditional Valencian wooden cottages with steep thatched roofs). Just as their original name suggests, the main activity was fishing (with a bit of smuggling thrown in) while the residents of the Grao were mainly employed in jobs connected to the port.

A great fire in 1796 completely destroyed the wooden structures of the Cabanyal. The fire was a huge tragedy for the district and stayed in the collective memory for years to come. The area was rebuilt but this time the, again, mostly wooden ‘‘barracas’’ were organised into a series of wide streets running parallel to the sea. Each street was wide enough to stretch out the fishing nets for drying, as described in Blasco Ibáñez’s novel ‘Flor de Mayo’.

The barracas were gradually replaced by brick houses (the last barraca was demolished in 1939) but the structure of the streets remained, and still remains today, almost like a sea wall running horizontal to rather than towards the sea. The civil war brought more tragedy to the area. With its proximity to the port, bombing raids caused the almost complete destruction of El Grao and the whole area had to be rebuilt after the war. Then came the great floods of 1957. The design of the streets meant that the water could not easily escape to the sea, and the many one and two-storey houses in the neighbourhood were almost completely covered, leading to great losses.

It wasn’t until 1897 that the Poblados Marítimos officially became part of the city of Valencia and even then they were physically separated from the rest of the city by four kilometres of agricultural land, occasionally punctuated by a few buildings like Palacio de Ayora and later the ‘Isla Perdida’. The Valencia-Barcelona railway line, which ran along what is now the Boulevard Serreria, was another physical barrier. All of which meant that the people of the maritime neighbourhoods developed a strong feeling of having a separate identity to the rest of the city’s citizens.

More than any other part of the city they have kept Valencian as their mother tongue and Spanish was rarely spoken in the area until the 1950s and 60s. The area also has its very own Easter festival, the ‘Semana Santa Marinera’ which takes place solely in this part of the city. The religious icons and Cofradias (brotherhoods) of sinister-looking Nazarenes march through the district escorted by the ‘‘granaderos’’ (grenadiers) in Napoleonic uniforms, which are copies of originals stolen as trophies from retreating French soldiers at the end of the French occupation of Spain from 1807 to 1814.

The neighbourhood also goes against the grain when it comes to football. Cabanyal FC formed in 1907, changed its name to Levante FC in 1909 and later became the modern day Levante UD. To this day, the majority of the Levante’s fan base lives in or has links with the Poblados Marítimos. They are even different when it comes to facial hair. A bizarre study by the Universidad Politécnica showed that the percentage of men with beards is up to ten per cent higher in the Poblados Marítimos than any other part of the city.

The low-rise, single family houses and the high number of small family owned businesses (more than 3,000 in the three neighbourhoods) creates an atmosphere more similar to a village rather than a district of a large Spanish city, with people sitting out on their dining room chairs outside their own front doors.

This is the kind of sense of community that organisations like ‘‘Salvem el Cabanyal’’, which successfully helped block the planned extension of Avenida Blasco Ibáñez through the heart of El Cabanyal to the sea. They also claim that in the last decade the area has been systematically excluded from any development or restoration projects leading to even more deterioration. Indeed, things are slowly improving and there are now plans for serious investment from public and private sources. Indeed, all sorts of alternative & very affordable bars like ‘Bar La Paca’ (C/del Rosario, 30) and multi-disciplinary venues like ‘La Fabrica de Hielo’ (C/Pavia, 37) have been popping up in the last few years.

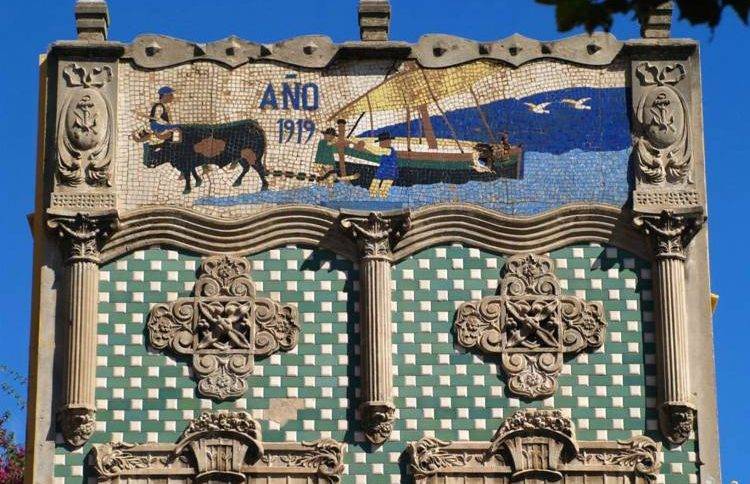

Though the area will undoubtedly change with gentrification, there are plenty of places which will hopefully keep the spirit of the place alive like the Cabanyal’s old Casinet (Sociedad Musical Unión de Pescadores) at the end of Calle Progreso on C/Jose Benlliure, 272. It’s a large, noisy old bar which hasn’t really altered since the 1900s and has long been at the centre of the community as the home of the Fisherman’s Union. And then there’s the Calle de la Reina, with its popular modernist houses decorated with shiny broken ceramic tiles and wrought iron.

There’s also, of course, Casa Montaña on Calle Jose Benlliure, 69… one of the oldest bodegas in Valencia, which has been providing people with wine and beer since 1836. Now a nice little tapas bar, if you can’t find room in the old shop entrance front bar, the place balloons out through the back.

In El Grao the real must-see is the Reales Atarazanas, the fourteenth century shipyards with their five long magnificent gothic arches in Plaza Tribunal de les Aigues. Just across the street you can get a real taste of the Grao by having a caña and a toasted bocadillo de habas in the dusty old Casa Calabuig at the very end of Avenida del Puerto, 336, by the port.

So if you are popping out of the pizzeria or McDonalds or into the Irish pub for a pint of Guinness and wondering about how hard it is to tell one European city’s faceless shopping centre from another, why not take a little trip down to the ‘Poblados Marítimos’ of Valencia…

David Rhead and José Marín

Article copyright ’24/7 Valencia’

Related Post

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

1 Comment

Andrew Prince

17th July 2017 at 3:48 pmWonderful article thank you