Just a day after I arrived in Valencia, my attention was drawn to a cultural movement existing here in the 80s and 90s. Labelled ‘La Ruta del Bakalao’ (also known as the Destroy Route, or simply La Ruta), this was a scene that represented many things at once: unlimited expression, the acceptance of all, and the search for joy after a period of bleakness. Splitting opinions all over Spain, its rise and fall is currently undergoing a period of revisionism. A quick search online relays its significance, having ‘long-term consequences on the form of nightlife in Spain’ and being the country’s ‘largest clubbing movement’. This I found intriguing, yet slightly baffling, considering Valencia’s current nightlife is not now so known as Spain’s larger cities or Ibiza. In addition to this, it surprised me that such an influential social phenomenon had remained largely unspoken of outside of Spain. I set out to uncover more on this hidden history.

Although the route is commonly referred to as La Ruta del Bakalao, it in fact originated as ‘La Ruta del Bacalao’. The latter, softer in its pronunciation and truer to the original values of the route, is a reference to ‘esto es bacalao del bueno’. This translates to ‘this is good cod’, a Valencian way of describing good music. The movement was born in 1981, a burst of creative innovation and freedom that starkly contrasted to the days of Franco’s dictatorship. Marisa Gallen, one of the artists involved in the movement, states that “as a generation, we had a mission to modernise and transform. We had to show the world that Spain had changed and the institutions needed, with the help of graphic design, to modernise their identities”.

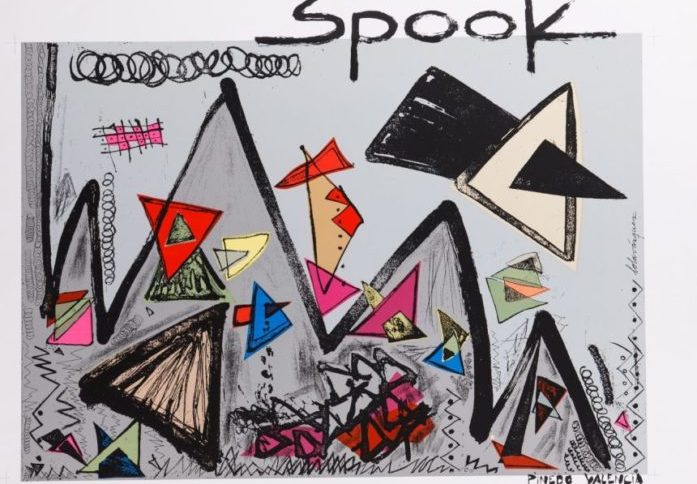

This quotation has been pulled from a montage of interviews that was exhibited a few years ago in ‘Ruta grafica’ at the IVAM (Valencian Institute of Modern Art). This is one of the means through which I sought out information on this hidden history. The exhibition contained more than 130 of the graphic designs used to advertise La Ruta’s events, a pivotal part of the movement. These designs, advertising the various nightclubs’ events, incorporate an industrialised, eccentric (though sometimes violent) aesthetic. From a pop-art figure of a woman holding a bomb, to a horrifying depiction of Micky Mouse drugged up and fragmented, you get a sense of the boundless experimentation that La Ruta entailed. There is a degree of political permissiveness. Nacho Garrido, another illustrator, confirms this, stating “I think it was a really politically incorrect time, but there was no censorship back then”. In the world of La Ruta, anything goes.

In almost every single text I have read, Barraca has been pointed out as one of the venues where it all began. A barraca is essentially a small and simple dwelling, which is how the club originated. Expanding over the years, gaining a new room and a pool at the beginning of the eighties, the space can act as an allegory for the movement’s rise and eventual deterioration. This is where Carlos Simó first played, who would go on to become one of the staple DJs of the movement. Dropping traditional dance music at the time, such as disco, funk and soul, Simó instead replaced this with new trends such as synth-pop and post-punk. British bands such as The Human League, Depeche Mode, Siouxsie and the Banshees and Joy Division were sought out. When researching the route online, there is a film picture of the Stone Roses stood outside Barraca post-performance …as bassist Mani said: “one of the best f**kin’ weekends of my life”. These international links made La Ruta unique; such alternative and fresh music was not being promoted elsewhere in Spain in the same way.

Another thing that became clear is La Ruta’s existence as an alternative to the mainstream. Barraca’s audience became eclectic, representing those on the margins. This was reflective of the movement’s open-mindedness. Drag queens would come to play here, and heterosexual men wore makeup. As the Spanish designer Francis Montesinos comments, “it was a moment of change, a moment of very different attitudes, social attitudes, all types of attitudes”. The audience was actively encouraged to be daring in the way that they dressed. What Valencia had over Barcelona and Madrid, then, is the element of seclusion. This is what allowed La Ruta’s safe space to flourish, away from the gaze of the majority.

Other clubs, such as Chocolate, Puzzle, Espiral and Spook Factory, allowed ravers to party from Friday to Monday for 72 hours straight. Hence, the name ‘La Ruta’, directly translating to ‘the route’. Chocolate was known for playing darker music, gravitating more towards psychedelic and gothic music. Described as ‘the antithesis of Barraca’, it seemed important for each club to have their own specific vibe. Edu Marin comments, “as far as I’m concerned, with Chocolate and then Arena, we tried to have a certain style”. Rather than being pre-meditated on behalf of the club owners, this was achieved by the artistic trial and errors of the graphic designers. Money and fame did not form part of the original ideals of La Ruta; many of the graphic designers remained anonymous. So spontaneous and accidental was the movement that some of the posters were altered by the workers of the printing presses themselves.

Jose Conca, another key DJ in the movement, would mix British post-punk sounds with electronic music, combining guitars with the most avant-garde techno of the time. Fran Lenaers, a talented DJ who led to Spook Factory’s success, continued in this fashion mixing rock with EDM, seamlessly merging the two genres in an expert manner. This became the hybrid genre later known as ‘bacalao’, the music representative of La Ruta.

Anonymous, hedonistic, unrestricted. So, my main question was, what sparked the fall of La Ruta?

Towards the very end of the eighties, ‘mescalina’, the previous drug of choice, was replaced by cocaine and ecstasy. The music became harder, darker, and the crowds more rigorous. ‘Parkineo’, the act of raving in the car parks between clubs, became a big thing. Unwittingly, through welcoming the masses, La Ruta del Bakalao was en route to its demise. Joan Oleaque, former resident at Spook, said “as it developed, it was a train without brakes; and it derailed”. What had initially been a budding movement unaware of its own importance began to spiral.

The way that ‘Ruta grafica’ is structured, split evenly between two floors, was my first indication that there had been a shift in what La Ruta was representing. A piece of text on the top floor is labelled ‘the Paradigm Change of the Nineties’. This explained that what initially began as artistic authenticity was morphed into something more commercial. The mass popularity of La Ruta in the nineties ‘led on the one hand to growing alarm voiced chiefly in the media’, and an end to the political permissiveness. Resultantly, a lot of the original and most talented artists backed out of the movement. So, with the foundations of La Ruta swept from beneath it, it is no surprise to find that what was left was simply an imitation of its former self.

Not confined to graphic design, this also infiltrated the music of La Ruta. In 1991, Chimo Bayo’s “Asi Me Gusta A Mi” was branded as the iconic song of La Ruta del Bakalao. In actuality, very few of the DJs played his songs. A report conducted by Resident Advisor contains interviews with DJs confirming this very point. Antonio Hal states, “[Chimo] wasn’t well regarded here by the other DJs, so they think, ‘Well if Chimo did it, so can we’. Everyone started producing tracks, the most linear, the most effective, built for the dance floor. Very fast… people jumped on the bandwagon, which distorted the industry. People took the easy route, the money route.” The renowned DJs of La Ruta faced having their work undone. Their meticulous searches for the very best vinyls in the world were replaced by poor quality, cheesy productions.

The nail in the coffin perhaps came with the release of “La Ruta Del Bakalao: Hasta Que El Cuerpo Aguante” in 1993, broadcast by Canal+. This was a documentary that conveyed La Ruta for all of its darkness: drugs, scandal and recklessness. The history of La Ruta’s more innocent beginnings was now overshadowed by this depiction. The police began to clamp down on the movement, until the ravers were no more.

For a long time, the mention of La Ruta would stir up memories of drugged-up youth and immorality, rather than being admired for its talented creatives and inclusive ideals. In recent years, however, various projects have been creeping out of the woodworks. ‘Ruta grafica’ is one of them, and also Joan Oleaque’s book ‘In Ecstasy. Bakalao as counterculture in Spain’ (2004). This text, the first of its kind, has a string of successors behind it. There was a festival, ‘Homenaje a la Ruta’, set for Benidorm and Valencia a few summers ago too. ‘The Guardian’ released their own piece on La Ruta, one of the few English pieces of journalism to exist on the topic. As a whole, these have all been successful in reclaiming La Ruta’s hidden history.

Furthermore, there was a television series released on ‘La Ruta’, starring Alex Monner and Claudia Sallas, amongst others. In an interview with the actors, the distrust of those at the core of the movement is emphasised: “we had to explain to people that we would not remain superficial”. Unlike the documentary of ’93, the series aimed to unearth the route’s full history. It did this through eight episodes, interestingly working their way backwards. By doing this, they can gradually dismantle some of the more simplified narratives created in the nineties, proving that there is more to this story.

When questioned on this resurging level of interest, Oleaque comments that there is a level of fascination held by kids of the modern-day. “They are fascinated by the modern part, by the design part, by the avant-garde, by the radical music, by the incredible ultra-advanced DJs, by the amazing people”. Indeed, there is a somewhat mystical enchantment now surrounding La Ruta del Bakalao. Its modern outlook presents an escapism just as attractive forty years on from when it existed. Its unattainable nature also glorifies it, to a certain extent. The youth of today wish to experience it, but they cannot.

Oleaque warns us of the danger of entering a state of good revisionism – letting nostalgia cloud logic. Whilst it is important to uncover the positive parts of La Ruta’s history, we should not forget the way that the movement came to an end. Moving from the margin to the centre came at the cost of those voices who founded the movement, corrupting its values. This is not unique to La Ruta; as Conca states, “you see this all the time”. What we can now be appreciative for is the influence that La Ruta del Bakalao has had on the electronic clubbing scene, and that its voices are finally being heard.

Report by Anusha Vasudeva

Article copyright 24/7 Valencia

More ’24/7 Valencia’ articles related to ‘La Ruta de Bakalao’…

https://247valencia.com/art-exhibition-at-ivam-ruta-grafica-designs-for-the-sound-of-valencia/

https://247valencia.com/the-legendary-dj-chimo-bayo/

https://247valencia.com/exclusive-the-stone-roses-interview/

Related Post

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

1 Comment

Fin Frew

8th January 2026 at 5:43 pmHola!

I hope you are well.

I am making a documentary on the music scene in Valencia and we are talking about the time of La Ruta in the 90s – I am desperate to find some images or videos that I can license for the film, could you help me?

Gracias,

Fin