1. Tell us something your background and travels…

I’m from Chicago. When I was twenty-one someone offered me the use of a house on a deserted island off the coast of Donegal in Ireland. I expected to return from there to America but never did. I lived in Dublin, London, Valencia and now in the city of Copernicus, Torun, in Poland. It started as a romance and remained that way.

2. How does living in Poland compare to living in Valencia, Spain?

Torun has seven hundred-year-old walls like Valencia. Unlike Valencia it has seasons, fabulous blooms in spring and crimsons and oranges in autumn and white winters. It is poorer. It is also greatly less voluble. Poles seem like whisperers compared to the Spanish.

3. You recently presented the Spanish translation of ‘I Could Read the Sky’ in Valencia. What is the book about?

The Irish came in great numbers to Britain to rebuild it after the war. It is about one of those who did that, an old man looking back on music and work and what he loved and lost. The book is made of photographs and words.

4. Could you tell us about your prize-winning book, ‘Motherland’?

That’s hard to compress. A fat, insecure, Irish clairvoyant goes walking through Irish history and landscape in search of himself and his nation and his missing mother. I’m not fat nor clairvoyant nor have a missing mother but somehow it was about me, I think. When I landed in Donegal I instinctively let my Americanness fade and began to look at Ireland. I’d been wanting but failing to write fiction in which I could believe for ten years but felt like I caught something when the first sentences of this came to me. It was exciting, nerve-wracking.

5. You have spent a large part of your life outside the USA. However, you returned to the land of your birth in ‘Divine Magnetic Lands’. Could you describe the experience?

I’d watched America in distress from a distance. Reagan distressed me. George Bush, Jr. distressed me far more. I thought they must have trawled the nation for the most appalling bottom-feeding fish they could find to form a government. I wondered what had gone wrong. I also had some yearning to be on the road in America. There’s no road like it that I know for making you feel you are passing through myth. It was rollicking and strange and eerily familiar and instructive and sometimes glorious. I wondered and still do how a nation filled with so many open, kind, pragmatic, unneurotic and astonishingly generous people could be so incapable of finding a viable form of government. I suppose the answer is that they do not govern. Lobbyists do, on behalf of the corporations that pay them.

6. Your latest book is called ‘Children of Las Vegas’. What was your intention with this book?

I was in Las Vegas for two years, first on a fellowship and then to teach. It seemed like the Twilight Zone to me, everything orderly and in straight lines but strangely empty and with an aura of the sinister in the air. There was furtiveness and anger, the kind of anger that perhaps has its origins in shame. One day my students began to talk of their lives – their parents stealing from them, falling apart from the various addictions it is the city’s business to offer. Many of them had had to raise themselves and their younger brothers and sisters from the time they were eight while their parents sat stupefied for days in front of machines into which they poured their rent and food and mortgage money. Las Vegas reverses nature in this and many other ways. It is so brassy and ostentatious and seems to demand that you write about it. I decided to make a book of testimonies of the people that really had authority, the people who had been watching it all their lives. I hope that those who read it think of what it is in us that brings into being such a place.

7. Is golf more fun than gambling in casinos?

You ask, I suppose, because I wrote a book about golf. There’s no contest. I would rather clean sewers than gamble in a casino. We didn’t gamble a dime in the two years we were there. Golf on the other hand asks that you bring all your physical and mental strengths to it. It’s been a lifelong fascination. Gambling just asks that you bring your weaknesses. One of the things, incidentally, that I most miss about Valencia is the golf course at El Saler, a place so exquisitely beautiful and natural and intelligently arranged.

8. Could you ever see yourself moving back to Spain or is ‘home’ the open road?

I go to Valencia because my children are there. I am very well in Torun. We set out for jaunts short and long, but I love coming back. It – I mean the house rather than the country or the city – feels like home in a way nothing else ever has.

Interview by 24/7 Valencia

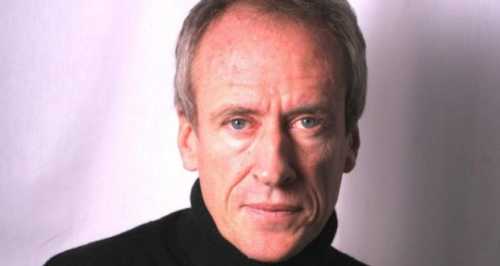

Photo by Iris Renata Lardner