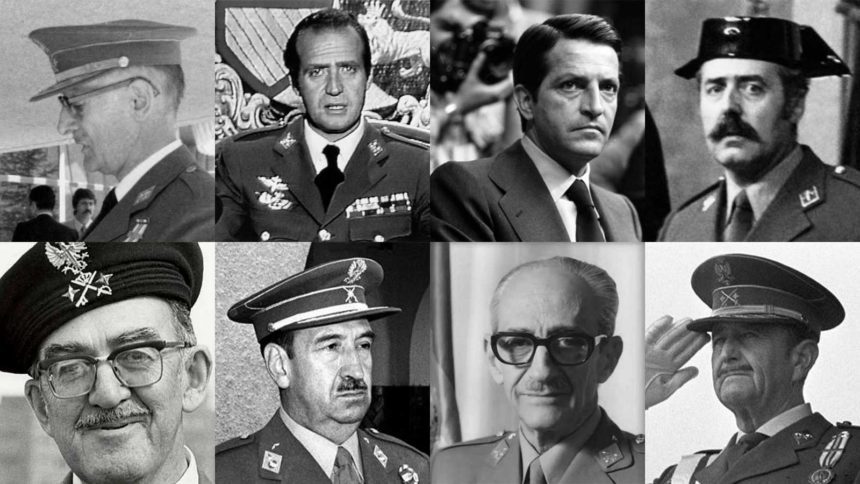

For those of us living in Spain today, democracy is a given and pretty much unmoveable. The dark, dull days of dictatorship seem a long way off. However, if some dangerously deluded bright sparks had got their way on 23 February 1981, things might have been a whole lot different and at the centre of all the madness was our fair city of Valencia. At 18.00h that evening, Guardia Civil Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero (half Charlie Chaplin, half Tom Selleck in a silly hat) took a military bus to the Spanish Parliament in Madrid and stormed the place with a group of armed men. The whole thing was captured by cameras following daily parliamentary business. The would-be rebels failed to notice this for at least forty-five minutes until they turned the cameras off. Even then, they left the sound running so the whole thing was broadcast over the radio by Cadena SER. Many feared an early end for Spain’s newly born democracy. Everybody knew a coup of this kind was a possibility. The ghosts of the far right had far from disappeared. Some figures in the military felt increasingly disgruntled at the way their power was systematically being dismantled and numerous terrorist attacks on various high-ranking military figures had done nothing to improve their mood.

Tejero and his men pranced about the parliament as only moustachioed Spanish military men can. They waved their guns around, fired shots into the air and shouted obscenities in a manly fashion at the astonished deputies (including the most famous ‘‘coño’’ in Spanish broadcasting history). It remained to be seen, however, how much support the attack would receive. Even some of Tejero’s men were only now realising what they were letting themselves in for and, according to testimonies from the staff of the parliamentary bar, they set about trying to drink the place dry. It quickly became obvious that in the country, as a whole, the would-be coup had virtually no support at all. That is, of course, with the apparent exception of Valencia.

At the Royal Palace General Armada, the supposed brains behind the operation, was desperately trying to see the King to gain royal sanction for the coup, which was seen as essential in order to gain widespread support from the rest of the military hierarchy. With or without it, he planned to ring round all the leading generals in Spain directly from the Palace implying he had Juan Carlos’s support. He was refused entrance by General Fernández Campos of the King’s household who, smelling a rat, told him the King did not want to speak to him. He then rushed to the parliament where Tejero also refused to let him in, accusing him of failing in his mission and being a traitor to the cause. At which point he decided he’d had enough and skulked off home.

While in the rest of the country nothing much at all happened, there was a dramatic turn of events in Valencia. Capitán General Jaime Milans del Bosch, an old Francoist crackpot and Civil War veteran, got so excited that he couldn’t wait for Armada’s telephone call. He imposed martial law in the city, told Valencians to stay in their homes and in a frenzy of militaristic ecstasy sent tanks and armed men from the División Maestrazgo based in Bétera onto the city’s streets. He took control of all bridges, the port and airport and sent tanks to stand guard over all public buildings. At first confusion reigned. The first communiqués in Valencia stated that the troops were there in order to protect democracy from attack. Many of the troops (mostly military service conscripts) assumed this was true or were told they were on manoeuvres. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to them, however, to ask themselves quite how they were going to protect democracy sitting in a tank in front of a pub in Plaza Cánovas. It wasn’t long before people realised that something more sinister was afoot. Was this the return of the dictatorship or, worse still, the start of a second Civil War?

Valencians who were around at the time remember how eerily quiet and empty the city seemed, the bars, restaurants and cinemas closed, the streets deserted. The only thing breaking the silence was the unnerving sound of the tanks on the Gran Vía and Avenida del Puerto… and the helicopters coming in and out of the heliport near what is now the Palau de la Música. Legend has it that the starlings, which normally nest impervious to the noise of the constant traffic of the Gran Vía, were driven away by the cacophony of the tanks. People tell of frantically hiding or destroying any left-wing literature that there might be in the house, others of the all-too-real concern they felt wondering what kind of country they would wake up to. Some stood up to Milans del Bosch from the start. Although the Capitán General had forbidden any meetings of more than three people, the then-mayor of the city, Ricard Pérez Casado, stayed in session with his councillors all night with all the lights on in the windows of the Ayutamiento as a show of defiance.

Slowly but surely, however, people started to realise that the whole thing was just a badly organised botch job perpetrated by a few rather pathetic lunatics. For a few hours a small Madrid division had taken control of TV stations, but Televisión Española was soon broadcasting again, relaying the events as they unfolded. People in Valencia were trapped in their homes but kept themselves informed and in touch with their friends and family by phone. At 01.00h in the morning, the King appeared on television addressing the nation. He denounced the coup and gave his full support to Spanish democracy, the most useful thing he would ever do in his entire life. The tanks were retired and Milans del Bosch was officially relieved of his duties. The following morning Tejero and his men gave themselves up and the sad, sorry drama was over.

Some Valencians have described the day after the coup as being a bit like the day after the Cremà in Fallas. Everybody went to work, the city was calm and back to normal with very little to indicate that the previous night’s events had ever happened at all. The coup had been a complete and utter failure and, if anything, it helped to hasten and cement the establishment of Spanish democracy. For many Spaniards the spectre of military dictatorship was finally laid to rest. As one Valencian put it , ‘‘the whole thing left me with a feeling of shame coupled with indignation that a group of seditious, grey, tawdry men would try to take over power against the wishes of the people. Fortunately it all amounted to nothing but a black joke, an illusion, but at other times and in other parts of the world the story has been tragically different’’.

Within months of the attempted coup, the Socialist PSOE party was elected to govern the country. Spain rejoined the international community through NATO and the European Union and any thought of a return to military government passed into the pages of history. Thirty people including the three stooges, Milans del Bosch, Tejero and Armada were arrested and imprisoned. Milans del Bosch died shortly after leaving prison, Armada now spends his time cultivating orchids in his isolated villa in Galicia and Tejero has taken up oil painting and writes the occasional bitter letter to the local papers.

David Rhead and José Marín

Article copyright ’24/7 Valencia’

Related Post

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Leave a comment